It’s always difficult to predict which news stories and campaign events matter. Why and when do people change their minds?

Most people don’t watch all the debates, or follow the political news closely—so political parties often repeat the same messages ad nauseam. They hope these will percolate into the public consciousness, drip by drip, through newspaper front-pages, news segments on the radio and television, push notifications from news apps, and social media. This is the so-called ‘air war’1. The goal? To change the background music—the tune influencing the conversations that millions of people up and down the land are having in their homes, in their workplaces, in coffee shops and pubs.

These conversations are the true process of democracy—not the headcount that follows them.

Despite efforts to focus minds on opponents’ tax plans or past economic mismanagement, the messages that ‘cut through’ and affect how people might vote are often off-script. We might well speculate on whether the story of ‘insider gambling’ on the election date by Conservative advisors will be among them. Or perhaps Nigel Farage’s comments about Vladimir Putin will cause a Britain bedecked with Ukrainian flags to recoil.

We can do more than speculate when we look back. Since my last post there have been a few interesting changes in the political mood. In this chart I’ve once again removed the (large) average differences between pollsters so that we can see the changes in how people say they will vote:

Are Labour losing support?

First, let's talk about something less-remarked-upon in the news. During the campaign Labour have lost some ground, while the Liberal Democrats have made some up. Perhaps voters, seeing Labour far ahead, realise they can afford to vote for a third party2? This is something the Labour campaign have stated they are worried about.

However, another factor is that ‘tactical voting’ movements are now in full swing. If many people feel more enthused about removing the Tories than by Labour taking up the reins, it follows that they may vote for whomever can best defeat the Conservatives where they live. There’s some evidence that this is behind the modest Lib Dem gains.

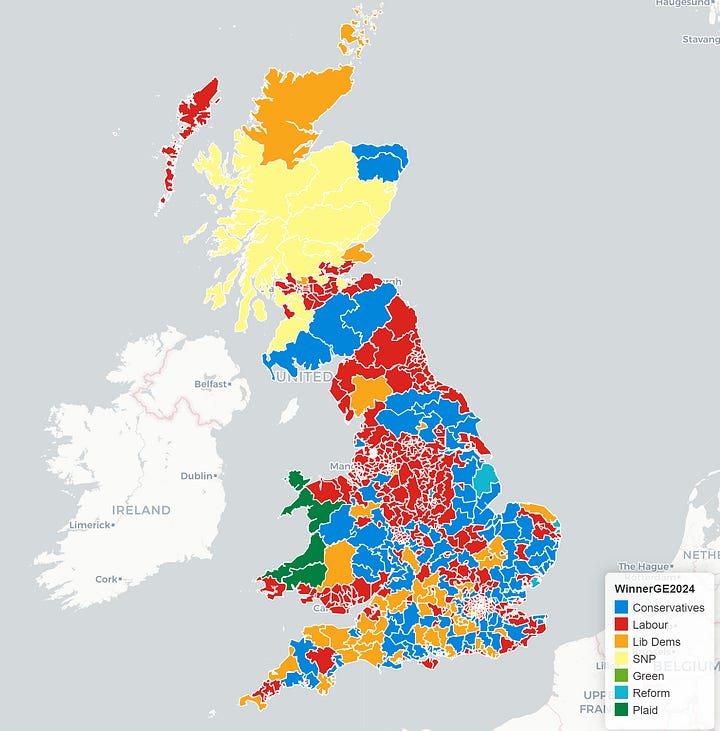

Here are the latest constituency predictions from YouGov. On the right I show only those where the prediction has changed since early June. A lot of these shifts are just random variation—the results are knife-edge, the changes don’t mean much—but in aggregate we can see that:

The Lib Dems and Labour both seem to be benefiting as the campaign rolls on

Reform are now projected to pick up a few seats

Splits on the Right

In the first chart we could see clearly the continued rise of Reform. I wrote previously about the jump in their support after Nigel Farage returned as their leader. Since then they have made further gains—with their average vote share rising to the high teens. The expected ‘crossover polls’ (where they overtake the Conservatives) have started to appear, but I do not think they are truly second place to Labour at the moment.

I speculated about the consequences of further gains for Reform, but noted that predicting these accurately would be challenging without a new MRP model3—or ‘Megapoll’ as certain journalists have dubbed them. We now have one.

In fact we have three: YouGov, Savanta, and More In Common have all published new Megapolls this week4. The fly in the ointment? They don’t agree.

That is to say, they all agree that Labour will win a large majority. But More in Common give them 406, Savanta say 4815, and YouGov 425. Quite a variation!

Now, there is some statistical uncertainty in these seat estimates. Helpfully, YouGov give us these numbers: most likely Labour will win between 401 and 445 seats, they say. This just about overlaps with More in Common’s best estimate, but there’s a tension between it and Savanta’s numbers.

Similarly, there is no consensus about how many seats Reform will win … other than the vague ‘few, if any’6. YouGov now think it could be anything between zero and 17 seats—though only Clacton (where Nigel Farage is standing) is thought to be odds-on for Reform.

Here is where the latest YouGov Megapoll thinks Reform is going to pick up votes. The brightest colours show where that support is concentrated (i.e. where they might win some seats):

In the last few elections YouGov’s MRP model has been fairly good … so long as you realise ‘good’ means ‘within the uncertainty range’, not ‘spot on’7. It’s no surprise that news organisations (and other clients of polling companies) have started asking their competitors to recreate this success. That other pollsters are getting in on the action reveals (helpfully) that the results of this approach greatly depend on the assumptions you make when you build your model. Polls—even Megapolls—aren’t destiny.

Supermajority

That said, the situation is pretty one-sided at present. None of these disagreements between pollsters matter when it comes to the most important outcome of the election: all predict a solid Labour majority. You might say ‘a Supermajority’—as various Conservative politicians have done.

This is a strategic shift. Effectively, the governing party has conceded that they have little chance of winning: the polls are clearly dire for them; postal votes are already being filled out. They have switched to a new tactic in the ‘air war’—namely, asking voters to back them … not to prevent a Labour victory, but rather because they should be worried about its scale.

There is something to this. A ‘Supermajority’ is a nebulous concept in UK politics (it doesn’t have a formal meaning, unlike in some other political systems). Nevertheless, there are real consequences to a government having a huge majority:

The opposition will not have enough personnel or funding to effectively ‘shadow’ government departments—to study the detail of what they are doing and to hold them to account properly.

Select Committees will be chaired overwhelmingly by MPs from the governing party, reducing opportunities for the opposition to scrutinise policy.

While all governments can have rebellions (where MPs from their party refuse to line up and vote for something controversial or ill-advised), these would be ineffective. If the government tried to do something heinous, the opposition might fail to frustrate it even if a really big rebellion joined forces with them.

For our system to function well (regardless of the governing party) the opposition needs to be big enough to do its job. There is a real danger that a huge majority for any party will lead to complacent, over-mighty government, with no viable replacement waiting in the wings.

This is a hard message for the Conservatives to land. Most people who are thinking of voting for Labour are unlikely to be swayed by a somewhat abstract constitutional point. Yet, it’s of-a-piece with their general strategy (which I wrote about here), which is much more focused on shoring up their core vote than on taking votes from Labour. Painting a picture of a colossal Labour Supermajority may indeed staunch the bleeding and preserve their last hundred seats.

As opposed to the ‘ground war’ of knocking on doors, putting up posters, and leafleting.

This is like the inverse of the 2017, when—faced with a big Conservative lead—Labour consolidated the left wing vote during the campaign.

To remind you: Multi-level Regression and Post-stratification models are a clever technique that involves polling tens of thousands of people (Megapoll!), working out how different demographics are going to vote, then using the known demographics of each constituency to project a result for each one.

Ipsos also published a Megapoll a week earlier, which had Labour on 453 seats.

You might have seen this reported as 516, but that’s if you assume the ‘most likely’ party wins in each and every constituency. The expectation number of Labour seats is 481.

As I argued in my last post, the main effect of Reform’s rising support is to erode the Conservative vote share, losing them seats (e.g. to Labour) that they otherwise might have won. As things stand, they won’t win more than a few seats. Any they win will be in places where their support is unusually concentrated.

Being scrupulously fair, even by this definition of success YouGov overestimated Labour’s eventual performance in 2019. They might not have looked so good if the result hadn’t been quite one-sided.