As a warning, this article will necessarily touch on potentially distressing topics.

This Friday (29th of November 2024), Parliament will vote on the ‘Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill’. If you haven’t been following along: this is a Private Members’ Bill which aims to legalise assisted suicide1 in certain circumstances.

As the Bill is not formally backed by the government, and since assisted suicide is considered a ‘conscience question’, there will be a free vote: all MPs will be able to vote whichever way they choose. In these last few days, then, I urge you to write to your MP and ask them to oppose this Bill, ensuring it goes no further.

Why?

I’ve cut to the chase. It seemed better to do so. But you may be asking yourselves why I so fervently hope the Bill will fail. After all, while it’s no secret that I have some relevant religious beliefs2, I’ve often been vocal about my support for the liberal principle: that where we lack consensus, we should aim to maximise collective freedom.

That very principle is the reason I oppose this Bill. The key word is ‘collective’. Contrast liberalism with libertarianism: the latter venerates individual freedom—and has little time for examining the effect of maximising this on wider society. When we ask people to abide by regulations, or to hand over some of their money as tax, we limit their individual freedom. But we do this in order to increase collective freedom: to create public infrastructure; to provide education and healthcare; to prevent exploitation of the powerless.

This is the most fundamental reason why, in the UK, legislation to permit assisted suicide has been rejected by Parliament on so many occasions (most notably in 1997, 2006, and 20153). Once you permit it, once you make it an option, there will be a series of knock-on effects—unintended consequences—that greatly outweigh the increase in personal choice for some.

Unintended Consequences

Of special concern are people with bad motives: how might they exploit the new situation?4 Sadly, such people exist and we ignore them at our peril. But let us imagine that everyone has only the best of intentions. Even then, it is hard to see how we avoid some people, nearing the end of their life and requiring a great deal of care, from feeling like a burden—either on their family, on an overstretched health service, or both. If assisted suicide were an option such people would inevitably feel pressure to use it. As Shabana Mahmood, the Justice Secretary, has said, “The right to die for some will … become the duty to die for others.”

Incentives can limit freedom just as strongly as any law.

Let’s talk about that overstretched health service. The NHS is under a huge amount of strain. The fundamental reasons for this (an aging population and a rise in chronic illness) are not going to go away any time soon. Meanwhile hospice end-of-life care is grotesquely underfunded; only a third of the £1.8B we spend annually on hospice care5 comes from the government; the rest derives from charitable sector. As the Sunday Times writer Stephen Bleach (referring to the reliance of hospices on charity shop profits) memorably put it : “in effect, the care we receive in our last days relies on the market for second-hand cardigans.”

A choice between inadequate, impersonal care and a quick death is no choice at all! Worse, once the problems caused by people having poor end-of-life care are ‘fixed’, where is the incentive to improve this care? What happens to the incentive to research new treatments into life-limiting illnesses?6 Small wonder that the Health Secretary and former supporter of assisted suicide, Wes Streeting, opposes this Bill on pragmatic grounds.

As a society, we make our choices about what to prioritise—and then we have to deal with the consequences.

Safeguards

Nor can we rely on safeguards built into the Bill (i.e. limitations on the precise circumstances in which assisted suicide would be permitted). In so many countries where assisted suicide has been legalised we see the same pattern: tight restrictions become looser over time, often through legal challenges. After all, if you provide a certain option to people in one circumstance, but not to others in a very slightly different circumstance, is that not discrimination?

I’m not being glib: in Canada, assisted suicide was first introduced and then expanded in scope again and again almost solely through legal challenges. In the UK many legal professionals and scholars argue that it will inevitably happen here, too.

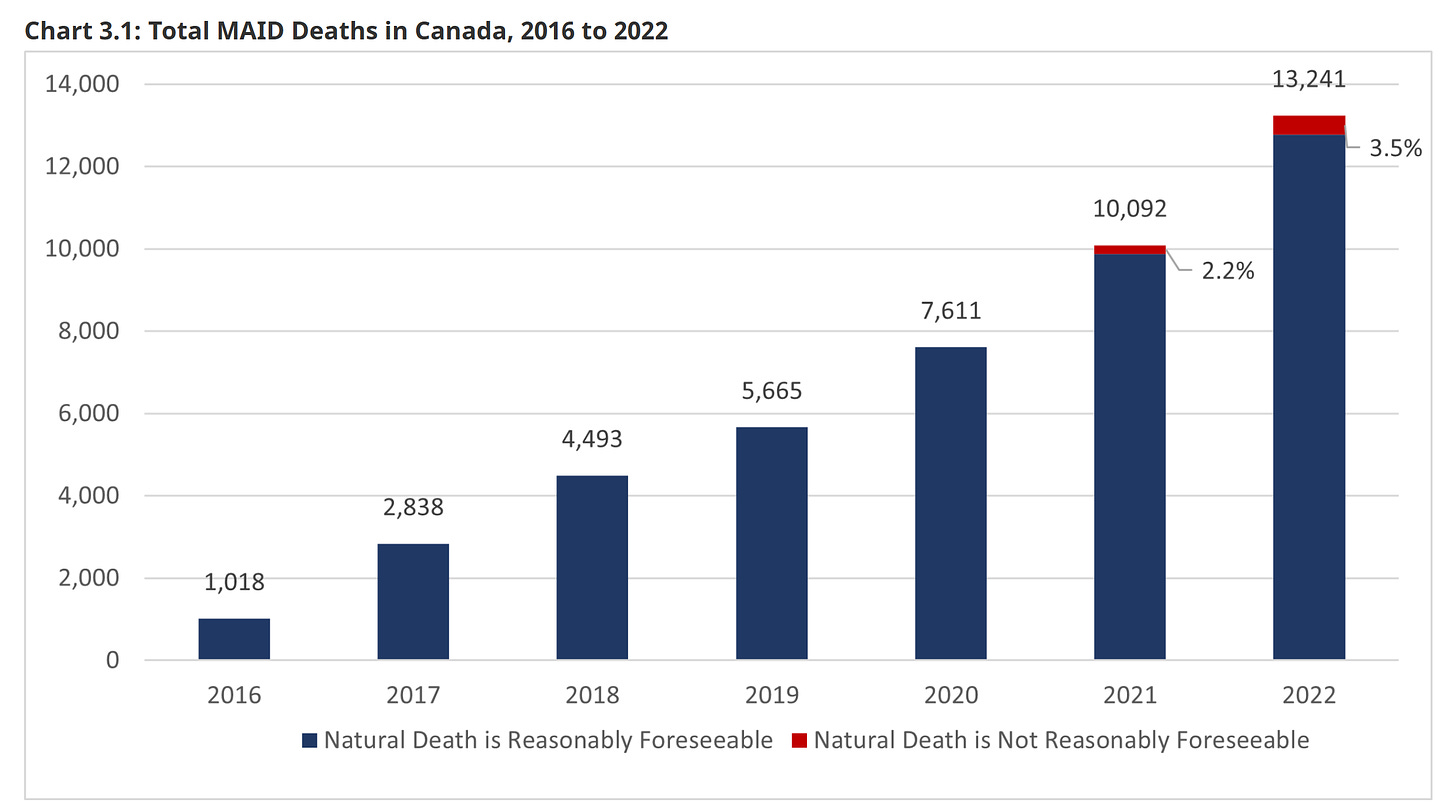

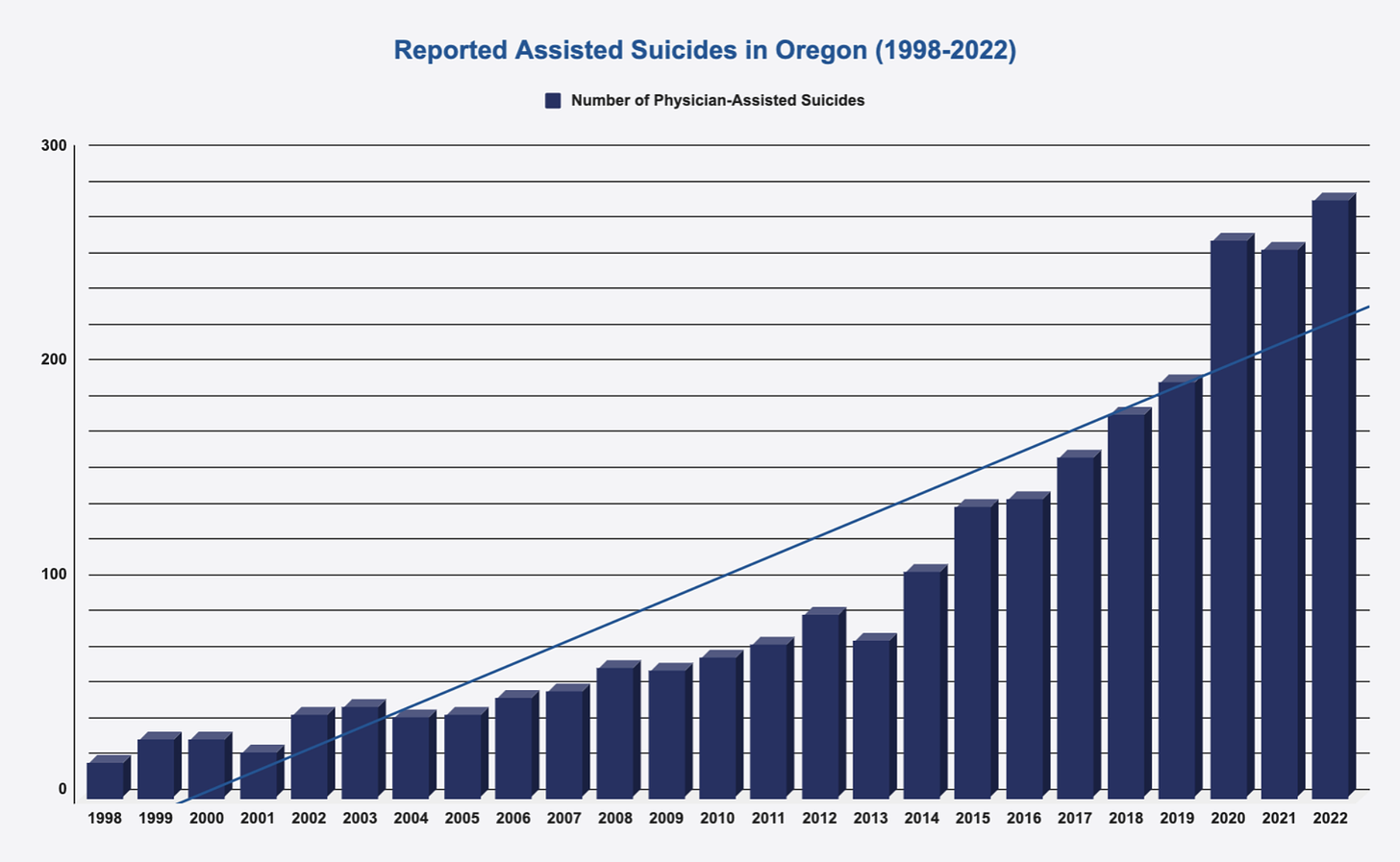

The net effect of this is a pattern, repeated anew whenever countries try this: what was intended to be a narrow law, covering certain difficult cases, expands, encompassing more and more circumstances and increasing numbers of people:

At present the principle implied by UK law is this: the desire to end one’s life is a symptom of a deeper problem, something to be treated if possible. Once that principle is compromised we are lost. Safeguards and restrictions create inconsistencies. Law does not tolerate inconsistencies: inconsistencies lead to legal challenges. To resolve the inconsistencies the safeguards will be removed.

And so it goes:

in Canada plans are in motion to roll out medically-assisted suicide for those suffering from non-terminal and mental illnesses; the latter has been temporarily delayed

in the Netherlands the law has gradually expanded to include terminally ill children below the age of reason (with parental consent). Belgium has developed similar provisions.

Intended or not, this Bill will become a Trojan Horse for more expansive legislation. Its supposed safeguards offer no comfort.

Hard Cases

There is a famous legal aphorism: “hard cases make bad laws”.

I fully appreciate that many people find themselves in an intolerable position near the end of their lives; I too fear a future in which I might lose my mind yet linger on, or else suffer a painful, drawn-out end. This Bill isn’t the answer. In attempting to fix one set of problems—the ‘hard cases’—it will open up Pandora’s Box and create new, worse problems.

So what is the answer? Is there one? As the Liberal Democrat leader, Ed Davey, and the former Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, have recently argued: we do not have adequate palliative care in the UK and we need to get serious about improving this situation. Likely this would entail a large increase in funding—of hospices, but also of research and development of treatments for chronic pain and life-limiting illness.

You could argue for both a change in the law and for this extra funding. However, in policy there are always spending and organisational tradeoffs. Notably, the Anscombe Bioethics Centre has found an association across multiple jurisdictions between the introduction of assisted suicide and a deterioration in palliative care. The trade-off is not theoretical: we have to pick one.

I want to be clear: the idea is not to artificially extend life beyond what is reasonable. All the campaigners against assisted suicide I have met reject what they call ‘vitalism’—the expectation that doctors will single-mindedly pursue life-extending treatment for patients until the very end, perhaps against patient wishes.

Many accept that if adequate pain relief treatment were likely to shorten life somewhat, that would be an acceptable trade off. However, this kind of ‘double effect’ scenario turns out to be “more myth than fact”7. What isn’t a myth is that all our lives are finite. At the end, the thing to do is to make dying people comfortable. Manage any pain, arrange psychological relief, and—yes—at some point (and in accordance with patient wishes) cease burdensome medical treatment. This is the approach we should follow—not assisted suicide.

Summing up

If you were on the fence or hadn’t heard much about the Bill, I hope you found this article persuasive.

We are faced with a rare situation this week: an immensely consequential Bill, the success or failure of which has huge ramifications for the future of our country; where the result is unpredictable; where your individual MP will have to make up their own mind.

MPs listen to their constituents. Lend this debate your voice. I urge you: write to your MP. Ask them to oppose this Bill.

Specifically: a form of suicide in which a doctor prescribes lethal medication at the request of a patient, which they then self-administer. Some people refer to ‘assisted dying’ instead; personally I think this alternative term is unhelpfully ambiguous. Palliative care (treating a dying person’s pain symptoms and comforting them while avoiding further specific efforts to artificially extend their life) could also be termed ‘assisted dying’.

To be clear, since I am a Catholic, these include beliefs that would lead me to personal opposition to assisted suicide. Most relevantly: I have a moral objection to suicide in general—yet I am not proposing that we make it illegal again.

It seems we’re right on schedule. In truth, the proposed legislation differs little from those earlier, rejected attempts.

You should always ask yourself this about any law.

For reference, that’s equivalent to around 1% of annual NHS funding.

Amazing breakthroughs can and do happen (see, for example, the development of gene therapies for Huntington’s disease). But they don’t come from nothing—we have to build and maintain a system that encourages them.

The stress of serious chronic pain is itself life-limiting, so strong pain relief drugs, appropriately prescribed, tend to be (if anything) life-extending.